Scientists at the Mount Sinai Health System's Institute for Genomic Health analyzed the ancestral genes of more than 30,000 patients to remap and refine health risks by ethnic background.

Every day, researchers at the Mount Sinai Health System’s Institute for Genomic Health (IGH) search for innovative ways to read our genomes and translate that information into more effective, rational, and personalized treatments for patients. To Eimear E. Kenny, PhD, Founding Director at the Institute for Genomic Health, our genomes—the three billion DNA letters strung together along our chromosomes—serve as a powerful and highly detailed set of medical records that will get us there.

Recently, researchers at the IGH and at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai’s Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, The Charles Bronfman Institute of Personalized Medicine, and the Hasso Plattner Institute for Digital Health at Mount Sinai, studied how ancestral genes may be used to locate the groups of Mount Sinai patients who are most susceptible to certain diseases. The results of the study were published on April 15, 2021, in the journal Cell.

“With this method we learned a lot about the diversity,

genetics, and health of people in New York City,” says Dr. Kenny. “Because New York City is so diverse we may also be learning a lot about the relationship between genetics and health in populations around the world.”

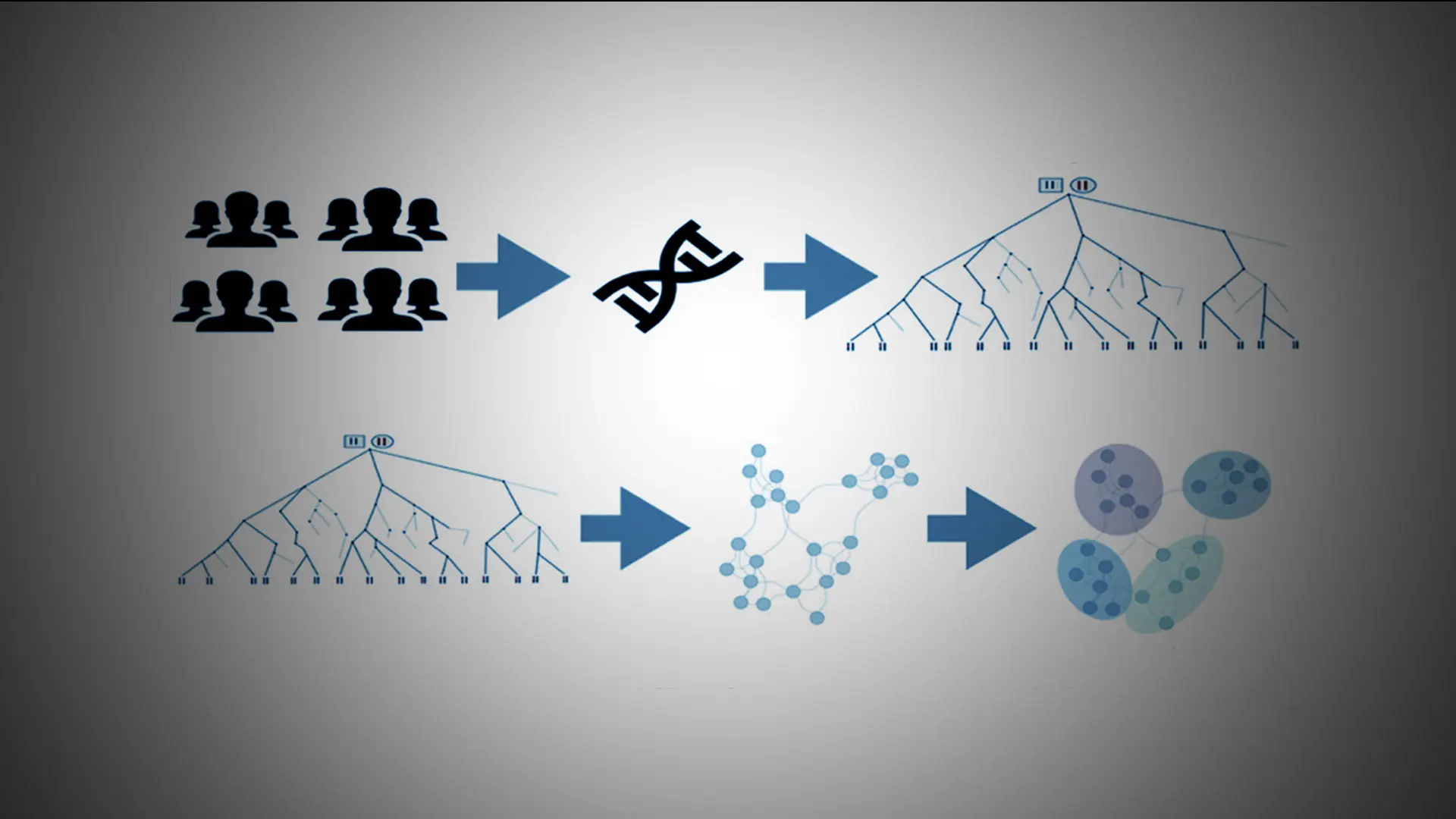

To do this, the researchers examined the data of 30,000 patients stored in the Mount Sinai Health System’s BioMe™ BioBank program, which is linked to the Health System’s electronic medical records. Initial results suggested that analyzing the patients’ ancestral genes produced a more accurate picture of a person’s background than traditional racial and ethnic classifications, such as Hispanic or South Asian.

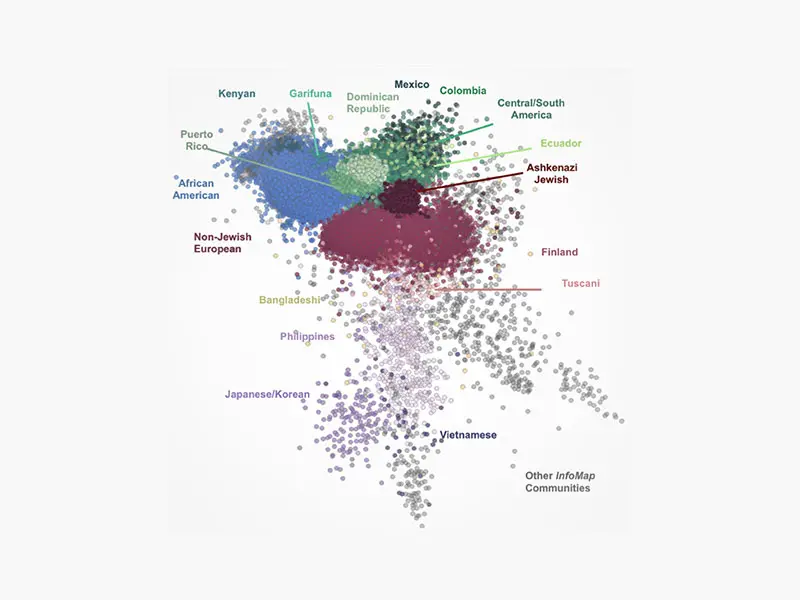

About 96 percent of the patients came from 17 ethnic backgrounds.

The researchers then discovered that about 96 percent of these patients came from 17 different ethnic backgrounds. This required searching for ancestral stretches of the genome, or “long haplotypes,” which were shared among the patients.

Further experiments suggested that this method was either equally or more effective at correctly identifying a patient’s country of origin than other genomic or self-reporting methods.

Finally, the team used these results to remap the health care risks of each group of patients as defined by their ancestral DNA. Some of their results reinforced previous findings. For instance, patients of

African descent, including those of Puerto Rican and Dominican Republic ancestry, had a high chance of suffering from sickle cell anemia, while those of Puerto Rican descent, exclusively, were at risk of experiencing asthma.

Other results led to the discovery of new health risks. This included the finding that patients of Dominican Republic heritage were at risk for peripheral artery disease, while those of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage were more likely to experience an autoimmune thyroid disease.

This method of analysis also helped the researchers show that the number of people who have disease-causing mutations might be higher than current estimates suggest. It also helped the researchers identify which groups were more at risk of experiencing complex disorders, such as type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease.

“Our results suggested that we can get a more dynamic and nuanced picture of the types of diversity in a given population,”

says Gillian Belbin, PhD, Director of Population Genetics at the Institute for Genomic Health, and the study’s lead author.

Featured

Eimear E. Kenny, PhD

Director, Institute for Genomic Health

Gillian Belbin, PhD

Director of Population Genetics, Institute for Genomic Health